To participate in any of ERI’s MaMA Anecdata projects, you will need to be able to distinguish ash from other trees. (However, as described below, in most situations you do not need to be able to distinguish between species of ash). Ash are easy to distinguish from most other common trees by their combination of opposite leaf arrangement (and opposite branch arrangement) and compound leaves; see https://www.uwgb.edu/biodiversity/herbarium/trees/alternate_opposite_leaves01.htm In fact, one of the specimens shown on that page is of ash – which one?

The only other common tree in our area that has opposite, compound leaves is boxelder (Acer negundo), which has fewer leaflets, which generally, unlike ash, have several very coarse teeth.

Hickory and walnut trees have compound leaves and are widespread in our area, but their leaves are alternate rather than opposite; often you’ll need to look closely at this feature of these trees to distinguish them from ash (binoculars can be helpful if the lowest leaves are high off the ground).

In the Northeast, you do not need to be able to distinguish between species of ash to participate in any of MaMA’s Anecdata projects, as it is acceptable to simply report the trees you find as “ash”. Indeed, it is essential to the projects’ broad participation that they are not limited to people who can distinguish between each species of ash, which, as described below, is not needed to achieve the projects’ conservation purposes. However, in some particular cases, described here, it can be helpful to distinguish between some species of ash.

Of the native ash found across the Northeast and Upper Midwest, there are two especially widespread, common species: white ash (Fraxinus americana) and green ash (F. pennsylvanica, sometimes also called “red ash”). These two species can be very difficult to tell apart, especially because they hybridize. Because EAB affects these species similarly (with indistinguishable mortality rates), there is no need to distinguish between these two species for MaMA’s Anecdata projects (when scion from these trees are collected for propagation, the USFS definitively identifies them using molecular analysis). For the same reasons, it is entirely unnecessary for our Anecdata project participants to even attempt to distinguish between the various subspecies (or other taxa) into which both green and white ash can be divided.

A third species, black ash (F. nigra) is also found across the Northeast and Upper Midwest, but has a patchier distribution, occurring only in swamps. It has special great cultural significance for Native Americans and plays a crucial role in maintaining swamp hydrology (including flood prevention). Also, less has been done on lingering ash collection and breeding for this species. For all these reasons, you are encouraged (but not required) to learn to distinguish black ash from the other two widespread species, which should not be too difficult, as shown below.

Also, areas of the Midwest and S. Appalachians are inhabited by blue ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata), which is quite distinctive from the other ash species (see http://forestry.ohiodnr.gov/blueash), and thus far has shown somewhat lower mortality from EAB; so if you’re doing this project in those areas, you should learn to distinguish this species from the others. Finally, pumpkin ash (Fraxinus profunda) is a species of wet areas that is very rare in the Northeast/Northern Mid-Atlantic (found at only a few sites in NY, PA, and NJ), but more widespread in the Midwest and the South. It is especially similar to white ash, but can be most readily distinguished from this and the other more widespread species by having substantially longer samaras (i.e., the seeds and the “wings” that are attached to them). However, especially when there are no seeds on the tree, identifying pumpkin ash can be quite difficult, and is not necessary for any of our iNaturalist projects. In addition to the species mentioned here, other ash species are found in N. America, but beyond the Northeastern and Midwestern areas covered by our iNaturalist projects, so we will not discuss them here.

We suggest that you practice distinguishing ash from other tree species both online and in the field before reporting data for any of MaMA’s Anecdata projects. Also, if you are participating in either the MaMA Monitoring Plot Network Anecdata project or MaMA Lingering Ash Search Anecdata project in an area where blue ash occur (Midwest, S. Appalachians), you should learn to distinguish this from the other widespread ash species. If you will be doing any of our Anecdata projects in a swamp in either the Northeast or Midwest, we encourage (but don’t require) you to learn to identify black ash.

Recognizing black ash

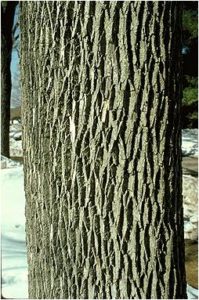

Black ash occurs in swamps, so you should be on the lookout for them if you’re in that habitat. Black ash, unlike typical green ash and white ash, does not have the diamond-patterned bark typical of these other two species. Instead, it typically has flaky bark (see photos below). However, green ash, which often occurs together with black ash, can rarely have flaky bark, similar to that of black ash. Therefore, if you find possible black ash, you can more definitively distinguish them from green ash them by looking at their leaflets (binoculars are helpful for this if the lowest leaves are high off the ground). On black ash, the leaflets are sessile (meaning that they’re attached directly to the leaf rachis, i.e., the leaf’s main stem), whereas on green ash the leaflets are attached to the rachis by short stems known as “petiolules”). White ash typically have even longer petiolules than green ash, but they don’t usually occur in swamps and don’t have flaky bark, so they should not pose the threat of confusion posed by atypical green ash.

Black vs. white and green ash bark